Society–Social Structure

Without society we could not survive. But what exactly is a society? Several conditions must be met before people can be said to be living in one society. First, they must occupy a common territory. Second, they must not only share that territory but most also interact with one another. Third, they must, to some extent, have a common culture and a shared sense of membership in and commitment to the same group. We may say, then, that a society is a group of interacting individuals sharing the same territory and participating in a common culture. A society is not necessarily the same as a nation -state, although in the modern world the two are often identical. The survival of non-human societies depends primarily on unlearned “instinctive” pattern of behaviour. But human societies are totally different. The organization and characteristics of each human society are not based on the rigid dictates of its members’ “instinct.” They are created by human beings themselves and are learnt and modified by each new generation. Consequently, although all human beings are members of the same biological species, every human society is do different that an individual suddenly transplanted from, say, the United States to a jungle of Brazil or vice versa, would have very little idea of how to behave appropriately. Societies are not simply a collection of randomly interacting individuals who happen to occupy the same area. Each society has its own distinctive character, the product of it history and environment, but all societies have an underlying pattern of relationships, a social structure that makes social life relatively smooth and predictable.

Social Structure

Social life is not a haphazard affair. It is generally stable, patterned and predictable. We know more or less what kind of behaviour people expect from us and n the whole we conform to these social expectations. There is an underlying regularity l the behaviour of both individuals and groups, that makes society orderly and workable. This patterned nature of society is based on social structure.

Social structure refers to the organized relationships between the basic components : a social system. These basic components are found in all human societies, although itir precise character and the relationships between them vary from one society to _nnther. The most important of the components of social structure are statuses, roles, _T >ups, and institutions.

a) Statuses

Each individual has one or more socially defined positions in the society — woman, teacher, carpcnivr. son, and so on. Such a position is termed as status. A person’s status determines where that individual’ “Fits” in society and how he/she should relate to other people. The status of daughter, for example, determines the occupant’s relationships with other members of the family; the status of teacher determines the occupant’s relationships with students, naturally, a person can occupy several statuses simultaneously but one of them,

usually an occupational status, tends to be the most important, and sociologists sometimes refer to it as the person’s'”master status.”

We have little control over some of statuses. If you are young, female, white, or black, for example, there is nothing you can do about it. Such as status is said to be ascribed., or arbitrarily given to us by society. But we have a certain amount of control over other statuses. At least partly through your own efforts you can get married, become a master or graduate, a convict, or a member of a religion. Such a status is said to be earned or achieved. We ^chieved statuses partly or wholly as a result of our own efforts, and society recognizes our changed status.

b) Roles

Every-status has one or more roles attached to it. The distinction between status and role is a simple one: you occupy a status, but play a role. Every position or status in society carries with it a set of expected behaviour patterns, obligations, and privileges. Status and role are thus two sides of the same coin.

We play many different roles during the course of each day. The content of our role behaviour is determined primarily by role expectations, the generally accepted social norms that define how a role ought to be played. The fact that people may have several different statuses, each with several different roles attached, can obviously cause problems when role expectations conflict. Sometimes conflicting expectations are built into a single role. A factory public relations officer, for example, is expected to maintain good relations with the workers, but he is also expected to enforce regulations that the workers may resent. This situation is called role strain. Another problem arises when a person plays two or more roles whose requirements are difficult to reconcile. For example, police officers sometimes are required to arrest their children. This situation is called role conflict.

c) Groups

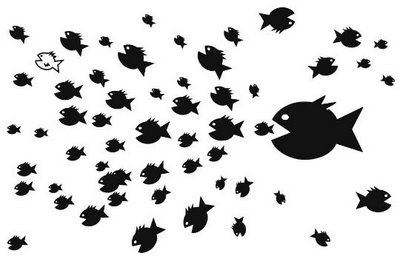

In its sociological sense, a group is a collection of people interacting together in an orderly way on the basis of shared expectations about each other’s behaviour. As a result of this interaction the members of a group feel a common sense of “belonging.” They distinguish members from nonmembers and expect certain kinds of behaviour from one another that they would not necessar ; expect from non-members. The essence of a group is that its members nte—t with one another. As a result of this interaction, a group develops *r. nt.—structure. People form groups for the purpose that cannot be achieved through individual efforts. The fact that groups share common goals means dm (he —tend to be generally similar to one another in those respects dot are iilliM to the group’s parpose. For example, if the goals of the group me pofiaoL ik acakn ad to share similar political

opinion. The more the members interact within the group, the more they are influenced by its norms and values and the more similar they are influenced by its norms and values and the more similar they are likely to become.

d) Institutions

Institutions are the stable clusters of values, norms, statuses, roles, and expectations that developed around the basic, needs of a society. For example, the family institution takes care of the replacement of members and the training of the young. The political and military institutions take care of the protection of the society against outside enemies and assume some of the responsibility for social control within the society. The economic institution organizes the production and distribution of goods and services, the religious institution provided a set of shared values. The educational institution passes on cultural values from one generation to the next and trains the young in the more refined knowledge and skills that they will need in later life.

Sociology, 1977, IAn Robertson, P. 77-81