As with other new technologies, Western countries were the first to grasp the strategic implications of radio communication after the first radio transmissions of the human voice in 1902. Unlike cable, radio equipment was comparatively cheap and could be sold on a mass scale. There was also a growing awareness among American businesses that radio, if properly developed and controlled, might be used to undercut the huge advantages of British-dominated international cable links (Luther, 1988). They realized that, while undersea cables and their landing terminals could be vulnerable, and their location required bilateral negotiations between nations, radio waves could travel anywhere, unrestrained by politics or geography.

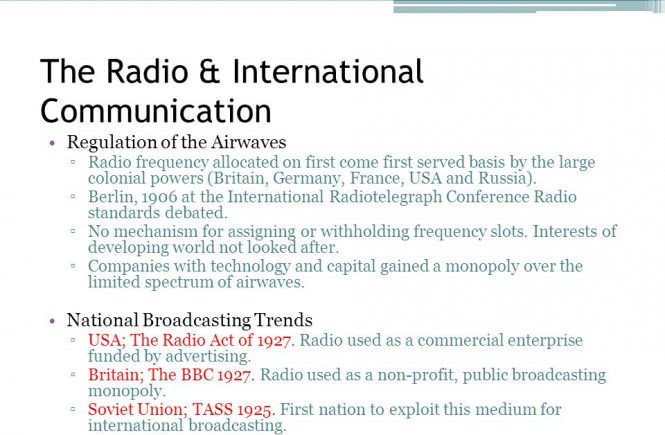

At the 1906 international radiotelegraph conference in Berlin, 28 states debated radio equipment standards and procedures to minimize interference. The great naval powers, who were also the major users of radio (Britain, Germany, France, the USA and Russia), had imposed a regime of radio frequency allocation, allowing priority to the country that first notified the International Radiotelegraph Union of its intention to use a specific radio frequency (Mattelart, 1994).

As worldwide radio broadcasting grew, stations that transmitted across national borders had, in accordance with an agreement signed in London in 1912, to register their use of a particular wavelength with the international secretariat of the International Radiotelegraph Union. But there was no mechanism for either assigning or withholding slots; it was a system of first come, first served. Thus the companies or states with the necessary capital and technology prevailed in taking control of the limited spectrum space, to the disadvantage of smaller and less developed countries (Hamelink, 1994).

Two distinct types of national radio broadcasting emerged: in the USA, the Radio Act of 1927 enshrined its established status as a commercial enterprise, funded by advertising, while the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), founded in 1927, as a non-profit, public broadcasting monopoly, provided a model for several other European and Commonwealth countries (McChesney, 1993).

As the strongest voice in the World Radio Conference in Washington in 1927, private companies helped to write an agreement that allowed them to continue developing their use of the spectrum, without regard to possible signal interference for other countries. By being embodied in an international treaty, these provisions took on the character of ‘international law’, including the principle of allocating specific wavelengths for particular purposes (Luther, 1988). A major consequence of this conference was to reinforce US and European domination of the international radio spectrum. However, it was the Soviet Union which became the first nation to exploit this new medium for international broadcasting.

The battle of the airwaves

The strategic significance of international communication grew with the expansion of the new medium. Ever since the advent of radio, its use for propaganda was an integral part of its development, with its power to influence values, beliefs and attitudes (Taylor, 1995). During the First World War, the power of radio was quickly recognized as vital both to the management of public opinion at home and propaganda abroad, directed at allies and enemies alike. As noted by a distinguished scholar of propaganda: ‘During the war period it came to be recognised that the mobilisation of men and means was not sufficient; there must be mobilisation of opinion. Power over opinion, as over life and property, passed into official hands’.

The Russian communists were one of the earliest political groups to realize the ideological and strategic importance of broadcasting, and the first public broadcast to be recorded in the history of wireless propaganda was by the Council of the People’s Commissar’s of Lenin’s historic message on 30 October 1917: ‘The All-Russian Congress of Soviets has formed a new Soviet Government. The Government of Kerensky has been overthrown and arrested. Kerensky himself has fled. All official institutions are in the hands of the Soviet Government’ (quoted in Hale, 1975: 16).

The Soviet Union was one of the first countries to take advantage of a medium which could reach across continents and national boundaries to an international audience. The world’s first short-wave radio broadcasts were sent out from Moscow in 1925. Within five years, the All-Union Radio was regularly broadcasting communist propaganda in German, French, Dutch and English.

By the time the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, radio broadcasting had become an extension of international diplomacy. The head of Hitler’s Propaganda Ministry, Josef Goebbels, believed in the power of radio broadcasting as a tool of propaganda. ‘Real broadcasting is true propaganda. Propaganda means fighting on all battlefields of the spirit, generating, multiplying, destroying, exterminating, building and undoing. Our propaganda is determined by what we call German race, blood and nation’ (quoted in Hale, 1975: 2).

In 1935, Nazi Germany turned its attention to disseminating worldwide the racist and anti-Semitic ideology of the Third Reich. The Nazi Reichsender broadcasts were targeted at Germans living abroad, as far afield as South America and Australia. These short-wave transmissions were rebroadcast by Argentina, home to many Germans. Later the Nazis expanded their international broadcasting to include several languages, including Afrikaans, Arabic and Hindustani and, by 1945, German radio was broadcasting in more than 50 languages.

In Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, a Ministry of Print and Propaganda was created to promote Fascist ideals and win public opinion for colonial campaigns such as the invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, and support for Francisco Franco’s Fascists during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). Mussolini also distributed radio sets to Arabs, tuned to one station alone – Radio Bari in southern Italy. This propaganda prompted the British Foreign Office to create a monitoring unit of the BBC to listen in to international broadcasts and later to start an Arabic language service to the region.

The Second World War saw an explosion in international broadcasting as a propaganda tool on both sides. Japanese wartime propaganda included short-wave transmissions from Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK) the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, to South-east and East Asia and also to the West coast of the United States, which had a large Japanese-American population. In addition, NHK also transmitted high-quality propaganda programmes such as Zero Hour aimed at US troops in the Pacific islands (Wood, 1992).

Although the BBC, apart from the Empire Service (the precursor of the BBC World Service), was not directly controlled by the British Government, its claim to independence during the war, was ‘little more than a self-adulatory part of the British myth’ (Curran and Seaton, 1996: 147). John Reith, its first Director General and the spirit behind the BBC, was for a time the Minister of Information in 1940 and resented being referred to as ‘Dr Goebbels’ opposite number’ (Hickman, 1995: 29).

The Empire Service had been established in 1932 with the aim of connecting the scattered parts of the British Empire. Funded by the Foreign Office, it tended to reflect the government’s public diplomacy. At the beginning of the Second World War, the BBC was broadcasting in seven foreign languages apart from English – Afrikaans, Arabic, French, German, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish (Walker, 1992: 36). By the end of the war it was broadcasting in 39 languages.

The French General De Gaulle used the BBC’s French service, during the war years, to send messages to the resistance movement in occupied France and for a time between October 1942 and May 1943, the BBC broadcast a weekly 15-minute newsletter to Russia with the co-operation of the Russian news agency TASS (Telegrafnoe agentstvo Sovetskogo Soiuza). It also broadcast The Shadow of the Swastika, the first of a series of dramas about the Nazi Party. The BBC helped the US Army to create the American Forces Network, which broadcast recordings of American shows for US forces in Britain, Middle East and Africa. More importantly, given Britain’s proximity to the war theatre, the BBC played a key role in the propaganda offensive and often it was more effective than American propaganda which, as British media historian Asa Briggs comments was ‘both distant and yet too brash, too unsophisticated and yet too contrived to challenge the propaganda forces already at-work on the continent’ (1970:412).

Until the Second World War radio in the USA was known more for its commercial potential as a vehicle for advertisements rather than a govern ment propaganda tool, but after 1942, the year the Voice of America (VOA) was founded, the US Government made effective use of radio to promote its political interests – a process which reached its high point during the decades of Cold War.