What is collective behaviour? Discuss different types and examples of collective behaviour. Also narrate theoretical approaches to the study of collective behaviour.

Collective Behaviour:

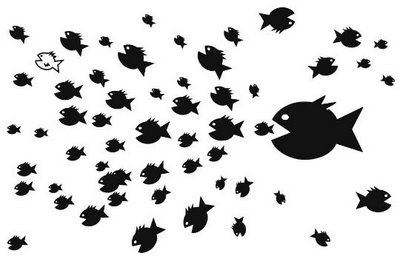

Collective behaviour has been generally applied to these events and refers to group behaviour which originates spontaneously, is entirely unorganized, fairly unpredictable and planless in course of development, and which depends on interstimulation among participants. Examples of collective behaviour include panics, revolutions, riots, lynching, manias, crazes, and fads.

Traditional approaches to the study of collective behaviour have emphasized the importance of emotion, suggestibility and irrationality in the understanding of collective episodes.

Types and Examples of Collective Behaviour

The term collective behaviour has been applied to a broad range of group activities ranging from a rather spontaneous and short lived actions of a crowd to the more organized, structured and long-term experiences of a major social movement.

– The Crowd

We attend the theatre and game events with a large number of people. We join the political demonstration to change the direction of domestic and foreign policy. Each of these actions could be viewed as crowd behaviour. Crowd refers to a highly diverse conditions of human assemblage: audience, mob, rally and panic all fall within the definition of crowd. Roger Brown (1954) classifies crowds as either active or passive. Passive crowds are given the label audience and can be either casual (a group pausing on a street corner to observe some stimulus event) or international (spectators at an athletic event) in nature. Active crowds are called mob and include aggressive collectivities, such as riots and fynch mobs, panics of escape and acquisition, and expressive crowds.

– Communication in the Crowd: Rumours

Most analysts of the crowd behaviour argue that the dispersal of information through rumours is one of the most important and significant processes underlying the whole phenomenon. When a mass of individuals joins together in a common course of action, such as riot, panic, or lynching, they must usually develop something approximating a common definition of the situation. The development of this common definition often occurs through the rumour-dissemination process.

Turner and Killian (1972) have noted that rumour is the characteristic mode of communication in collective-behaviour episodes. It is the mechanism by which meaning is applied to what is otherwise likely to be an ambiguous situation. Thus, rumours play an important problem solving role and allow the people to deal with the complexities and uncertainties of life by providing meaning and structure. Rumours are most likely to develop in situations that are characterized by both ambiguity and stress. Stress increases the immediacy of need for meaning, thus, when our personal welfare appears to be threatened in some way and there is no clear definition of what is happening or why, rumours are likely to run rampant. Rumours are generally passed by word of mouth from one person to another. When large groups of people are coming together, the speed of the transmission is greatly facilitated. These rumours are completely distorted in the process of transmission. They play a critical role in most episodes of collective behaviour. Through providing meanings in situations of ambiguity and stress, they provide an orientation for the potential actors by helping them develop a common definition of the situation. This aids in the mobilization of the participants for action by identifying a target on a riot or lynching, by attributing cause for problems and failure, and by defining what would be an appropriate course of action. Rumours are an important mechanism of information transmission in most societies and their significance is increased dramatically during stress and crisis.

– The Role of Leadership in Crowd

The acceleration of activity in many collective behaviours is attributed to the actions of the leader. This emergent leadership acts first what the others will do subsequently. This leadership is emergent and is not selected according to the traditional practice. The leadership emerges out of the course of group interaction and often disappears back into the crowd after the action has run its course. The development of leadership in major social movements is the exception. Many of the important political leaders achieved world recognition through their emergence as leaders of social movements. Examples include Ghandi, Fidel Castro, Mao Tse Tung, Imam Khomieni and many others. Conventional leadership follows conventional norms and leadership in a mob is engaging in the violation of conventional norms and they are the persons for whom norms are the weakest. The critical importance of leadership in most collective behaviour occurrences can best be summarized by reviewing the roles the leader plays. First, the leader builds and increases the emotional tensions of the groups. Second, the leader suggests a course of action that will relieve the built-up emotions.

Finally, the leader justifies the specified course of action as being “right”. This is the final stage for hesitant, timid and more rational people to be converted into collective behaviour. It is true that in most collective behaviour-episodes, things are not always as they seem. Marx (1974) notes that some activitists and even some leaders of social movements are actually “agent provocateurs” or informers planted by an authority to create internal crisis.

– Panic as a Type of Collective Behaviour

Panics tend to emerge from crowd situation such as fire in a cinema hall, hotel etc., but in some situations it emerges inspite of physical and psychological distance of the people involved in the panic. For example, economic panic can occur among persons who are widely dispersed if they come to apply a similar set of definitions to a common situation. Some stimulus is required to prompt the action of the dispersed participants, such as radio or television report (see Norms and Social Influence, unit -3 of part two). However, the presence of crowd facilitates reaction. In the simplest sense, panics involve competition for something in short supply. This may be economic resources, products or social status. Economic panics occur when money or some other commodity is believed to be on short supply and may result in such behaviours as a run on a bank or a selling run on a stock exchange. Other panics may occur when groups of people believe that there are insufficient escape routes in a dangerous situation, such as when a building is on fire. According to research, ambiguity about the degree of danger and the probability of escape increase the probability of panic behaviour. From From the study of experimental literature Fitz and Williams (1957) conclude that panics are most likely to occur when the following conditions exist:

- Individuals perceive an immediate and severe danger to life, financial security, social status and so on.

- People believe that there is a limited escape route or any other applicable form of “short supply”. If there were a large number of escape routes that would easily accommodate all those in need, there would be no need for competition and, hence, panic.

- People believe that the existing routes are closing, so that if one does not get out in a hurry, there will be no escape at all. If the escape routes are not closing, there should be ample time for everyone to make an escape, and panic will not be likely to occur.

- There is a lack of information or the existing communication channels are unable to keep everyone adequately informed on the issue. This leads to ambiguity and greater urgency in the situation.

Fashions and Fads

These types tend to be more trivial in terms of their total impact on individual lives, but they are also included under the umbrella of collective behaviour. Unlike many collective episodes, which tend to be “crowd” phenomena, fads and fashions do not depend upon the physical proximity of participants and can affect the behaviour of individuals in widely dispersed circumstances. A fad can be defined as some short-lived variation in pattern of speech, behaviour, or decoration. For example, music of air wolf (a PTV programme at time), phrases from drama and film, etc. Its occurances are quite unpredictable, but its life can be expected to be short. Fashions tend to be longer-live than fads. However, fashions is a process, which means that it is a continuing state of change. Hemline length, lapel width, hair lengths, the style of eyeglashes are the examples.

Traditionally, it has been assumed that fashions were introduced by people of high social status and that they then filter downward. In many instances, this is true, but the filtering goes in the other direction as well. For example, some contemporary style of dress, shoes, and foods originated in the lower social classes and then filtered upward.

Theoretical Approaches to the Study of Collective Behaviour

The major theoretical orientations of collective behaviour have been summarized under the headings of contagion, convergence, emergent norms theories, and sociological theory of Smelser.

Contagion Theory

Theories of collective behaviour based on contagion “explain collective on the basis of some process whereby moods, attitudes, and behaviours are communicated rapidly and accepted uncritically”. Contagion theory grows out of the classic work of LeBon (1896) who sought to understand how groups of individuals could come to present characteristics that were both different and unpredictable from the characteristics of the individuals composing the group. His explanation came to be referred to as the “law of the mental unity of crowd”. This proposed that under the right set of circumstances, the sentiments and ideas of all persons in a group would take one and the same direction, and individual initiative and personality would vanish. In such circumstances, the behaviour that resulted would be unique to the group setting in that one could not predict its occurrence simply on the study of the individuals comprising the group.

Contagion theory relies heavily on such idea as stimulus-response and emotional contagion. Supposedly, as a crowd mores around and interacts, emotions are transmitted quickly from one individual to the other, and each individual becomes transformed as he comes more and more under the influence of the group. This transformation is facilitated through “circular reaction” or “a type of interstimulation” whereby one individual reproduces the stimulation that has come from another and when reflected back to this individual, reinforces the original stimulation.

– Convergence Theory

According to contagion theory, the individual in a crown situation loses himself/ herself to the emotions of the crowd and does something that could not be predicted on the basis of individual characteristics. Convergence theory, on the other hand, argues that participants, particularly in violent collective episodes, were already predisposed to engage in such actions — the crowd simply offers them the excuse. Thus, collective behaviour is explained on the basis of simultaneous presence of a number of people who share the same predispositions, which are activated by the event or object toward which their common attention is directed.

According to convergence theory, the presence of the crowd is not the casual factor n collective outburst. Rather, it simply provides an excuse for people to do what they were already predisposed to do anyway. Allport argues, nothing new is added by the crowd situation “except an intensification of the feeling already present, and the possibility of concerted action”.

– Emergent-Norm Theory

The emergent-norm approach as initially developed by Turner and Killian (1957) argues that observers of collective-behaviour episodes have tended to get so caught up i the emotion of the situation that they fail to make important observations of what actually is happening. Thus, they fail to notice the definitional process that is often securing. “The shared conviction of right, which constitutes a norm, sanctions behaviour consistent with the norm, inhibits behaviour contrary to it, justifies proselyting, and requires restraining action against those who dissent. Because the behaviour in the crowd is different either in degree or kind from that in non-crowd situations, the norms must be specific to the situation to some degree-hence the emergence norm. Bystanders, influenced by the emotion of the situation, often fail to observe this process.

Emergence-norm theory differs in several important respects from the other two approaches. For example, rather than attributing crowd action to the “spontaneous induction of emotion”, greater emphasis is placed on group conformity through the imposition of a social norm. The crowd suppresses incongruous feelings and actions of its members and provides direction and meaning. In addition, limits on the direction and degree of crowd action are more readily explainable by emergent-norm theory than by the other two. The crowd defines certain behaviours as appropriate to the situation, but other behaviour may remain defined as inappropriate. The individual who goes beyond the limits is often chastised and sanctioned.

Smelser’s Valued-Added Theory

Smelser combines ideas from economic with the work of sociologists in developing “value-added” theory. Smelser’s theory seeks to provide answers to two basic questions: (i) what are the factors that determine whether or not a collective-behaviour episode will occur? and (ii) what determines whether one type (for example, panic as opposed to a riot) rather then another will occur? Value-added notion implies that the development of a collective-behaviour episode, involves a process and that each stage in that process adds its value to or influences in an important way the final outcome. More specifically, he sees six stages as necessary before collective actions of the nature discussed above will occur. These six stages occur in sequence, and ail are necessary, otherwise the developing episode will not occur, these stages include:

– Structural Conduciveness: The concept of structural conduciveness implies conditions that are permissive of a particular sort of collective behaviour. That is, general conditions in a given society are such that they would enable or allow a particular form of collective behaviour.

– Structural Strain: More specifically, structural strain refers to certain aspects of a system such as economic competition, unequal distribution of wealth, and sense of economic deprivation.

– The Growth and Spread of a Generalized Belief: The third phase involves the development among the potential participants of a generalized belief regarding the causes for the strain that exists and some means by which it may be eliminated. In other words, the developing belief that comes to be accepted by members of the group identifies the source of the strain, attributes certain agreed-upon characteristics to this source, and then makes some recommendation about how the strain can be relieved.

– Precipitating Factor: The precipitating event is the incident or action that sets

off the collective episode. Because of conduciveness, strain, and the development of a generalized belief, the situation is now ripe for an explosion. All it needs is the spark that will set it off.

– Mobilization of Participants for Action: Now all that is needed is for the gathered participants to mobilize. The mobilization is largely a function of two forces — leadership and communication. Before the milling and largely disorganized crowd can begin to take some coordinated action, some form of leadership must be provided. This emergent leadership then communicates direction to the crowd — for example, the target for the hostilities is defined, appropriate actions are specified, a division of labour may even be established, and so on. At this point, a full-fledged collective episode is underway.

The Operation of Social Control: Up to this point, it is argued that the factors identified must be present, otherwise the collective action will not occur. But the absence of the social control is the key to the final outcome. In other words, if social control is present, the presence of the previous five factors will be suppressed and controlled and cannot be converted into a collective-behaviour episode.